Summer is kicking in the door and bringing heat, humidity, and bugs. Let’s look at the three main types of exertional heat injuries there are and how to treat them. Be aware of the signs and symptoms of each, so if you are out with friends and countrymen on journeys far and wide, and one of them gets goofy, you can figure out what’s going on and get him treated.

Factors affecting exertional heat injury

Heat injury occurs when the the body’s ability to cool itself and maintain a functional temperature is impaired. The things that affect the probability of heat injury are:

You – your levels of fitness, hydration, nutrition, health, and acclimatization are huge factors in whether or not you’ll be stricken with heat injury. If you have been in Couch Potato mode for the last six months, then get inspired to go do a ten mile ruck in 90 degree heat with 80% humidity after watching an episode of Dual Survival, Carnac the Magnificent foresees trouble ahead. If you take medications like beta blockers for high blood pressure or Lasix (a diuretic) for other issues, your body’s ability to compensate for the increased metabolic load may be impaired. If you are in a cutting mode for weightlifting or taking weight loss pills that are diuretics, you need to be mindful as well.

We keep hitting on fitness on the site, and this is another reason why. The more fit you are, the more resilient you are. Watch your caffeine and booze intake. If you have a few the night before you do something physical, make sure you slam lots of water before bed and even more in the AM. You want your urine to be light to clear before you set out getting sweaty.

What you are doing – So there’s sitting on a chaise on Miami Beach sipping Cuba Libres watching the exotica pass you by and there’s rucking at Black Mountain from 2,000 feet to 6,800 feet on top of Mt. Mitchell with 80 pounds of gear.

One of these is going to tax you more than the other. One you can do all day.

One is going to require stops every 30-60 minutes to cool off, rehydrate and get some calories in you. When it’s hot and humid, you are going to move slower when you are exerting yourself. That’s a fact.

Your environment – It’s 12:00 noon and you are in a humid swamp in Georgia or the Mojave Desert under a cloudless sky and you have to walk ten miles to a gas station. Which sucks worse? They both do in their own special ways. Humidity, temperature, exposure to sun, and wind are all going to affect how well you do in these environs. A hot, humid, windless day in the swamp is going to make it hard for evaporative cooling to occur because sweating is less effective as a cooling measure in this environment. You may be able to find some shade under the pine trees to take some of the edge off, but you just have to move slowly. In the desert, you won’t find much shade, but at least it’s a dry heat and you’ll probably have some wind to help with evaporative cooling, even though it may feel like someone blowing a giant hair dryer on you.

If you are used to being in air conditioning all the time, you need to start spending more and more time outside doing moderate levels of activity. Spend about two weeks ramping up the activity and the duration spent outside so you are more acclimatized to the heat. This is no guarantee that you won’t blow yourself away in the heat, but it does mitigate it some.

Heat cramps

This is the first and mildest form of heat injury. It comes from overexertion of muscles in a high heat environment. Muscles cramp up and you sweat like a pig. The cramping comes from low levels of salt in the body, called hyponatremia, that occurs when someone has been hydrating like mad with water only and not replacing electrolytes, like salt and potassium.

Understand that if the patient is getting heat cramps, this is his body slapping him in the face to pay attention and start getting his hydration and electrolytes in balance before something worse starts to happen. You’ll know when a patient has heat cramps, because he’s going to be vocal about it. They hurt.

Treatment

Get him out of the heat and start stripping him down so that his skin is exposed to air to allow for convection and evaporation to be more effective. If you can get him in front of a fan, even better. Start rehydrating him with a sports drink or at least some salt. If you have Gatorade, try to dilute it with equal parts water. Have him eat some salty food if you have it.

Understand that once the patient has heat cramps, he needs to rest awhile and let his body’s metabolism get to a more normal state. Activity levels should be reduced for a day or two.

Heat exhaustion

This happens when your patient has ignored the heat cramps and pressed on. It’s more serious because the core body temperature is now rising to dangerous levels, the metabolism is running on overdrive, and the body is having trouble blowing off the heat. It’s not likely that the patient gets to this point on one outing, but over a few days of continued exertion and depletion of water and electrolytes. Again, it’s overexertion of muscles and the inability of the body to adequately cool itself that causes the problem. The body is trying to keep itself cool by pumping blood to the skin and dilating blood vessels, but the heart is not able to keep up and is getting overtaxed.

The patient is going to have the same symptoms as heat cramps, but with added fatigue, nausea and possible vomiting, dizziness, and very red, flushed skin. He should be sweating still. The key thing to look for between heat exhaustion and heat stroke is mental status. If his mental status is altered – then he is considered to have heat stroke.

Treatment

Follow the same treatment plan as heat cramps, but with some added steps. Get him out of the heat and into the shade. Strip him down and have someone pour tepid to cool water on him. Ideally, he should be drinking a diluted Gatorade or salt beverage for rehydration. If there is hypotension and profound tachycardia present, then IV fluids will be needed to restore fluid volume. Have him eat some salty foods and some fast absorbing carbs like oral glucose, jelly, or honey. Remember, this is a heat injury caused by over exertion, so he’ll probably be hypoglycemic, too.

Rest is very, very important here. Whatever he was doing, he’s now done until he’s had at least 24 hours of solid rest, re-nourishment, and rehydration. Because he’s had heat exhaustion, he’s more likely to get it again, so make sure you adjust his activity and rest cycles so that he’s not doing the same things that put him in heat exhaustion in the first place.

Heat stroke

This is a very serious medical emergency that requires immediate, invasive treatments and evacuation to advanced care. With heat stroke, you have all the same signs and symptoms as heat exhaustion, with the additions of altered mental status and a core temperature that keeps rising. To put it bluntly, the body is cooking itself alive and very likely to have organ system damage that will kill the patient if not treated aggressively.

Signs and symptoms of heat stroke are confusion, dizziness, fainting, hypotension, nausea, vomiting, urinary and bowel incontinence, red, hot, flushed skin, either sweaty or not. The patient can be sweating profusely in heat stroke, contrary to popular belief. The differentiator between heat exhaustion and heat stroke is the altered mental status and core body temperature, not the absence of sweating.

What we’re worried about here is a very high core body temperature (> 104F), hypoxia, cardiac overload, and organ system damage, especially the brain and the kidneys. The skeletal muscles will break down in a condition known as rhabdomyolysis (rhabdo) and will flood the bloodstream with large protein molecules that will clog the kidneys and kill them. Low salt in the blood serum can cause the brain to swell, causing seizures and possible brain herniation.

Treatment

In the field

Remove the patient from the heat and strip him down. If he has a firearm or any other weapon, you’ll need to disarm him. Call for rapid evacuation / transport resources. Pour tepid to cool water on him and get him in front of moving air. Get a rectal thermometer in him and monitor his temperature with serial measurements. If you have ice water, wrap the patient in a lightweight cloth or sheet with the ice and pour the water over him and make a “burrito” with the patient.

If he cools way too fast, he may start shivering, which will spike his metabolism and raise his core temperature again, so keep that in mind.

Go through your ABCDE assessment. Protect the airway. If he is altered and vomiting, he needs to be suctioned and intubated if you have that ability. If you have someone around that can perform Rapid Sequence Induction (RSI), that’s even better, because the neuromuscular blocking drugs will keep him from shivering as you cool him. Caution on succinylcholine though because of possible hyperkalemia.

Assist with ventilations with 100% oxygen at 15 liters per minute if you have it.

Get two large bore IVs established and start aggressive fluid resuscitation. We want to dilute his blood so that the rhabdo is less likely to damage his kidneys. Keep on eye on the color of his urine. If it turns dark, that’s an indicator that the rhabdo could be in full effect.

Get baseline and serial vital signs to monitor his status and transport ASAP.

At the advanced care station

There’s a lot of stuff here that is very grid-up treatment that will bore most everyone to tears, since it is a lot of lab values and tests to confirm the presence of rhabdo, etc. We’re happy to have this discussion in the comments with anyone that wants to discuss. We’re just trying to stay more grid-down.

The reality is, without rapid transport and advanced care, a heat stroke patient in the field has a very poor prognosis.

Like heat exhaustion, anyone that has a history of heat stroke in the past is more likely to have a repeat performance, so make sure you ask about people’s histories before engaging in strenuous outdoor activities.

Resources to avoid heat injury

As mentioned earlier, acclimatization to hotter environments is critical. If you have been hiding inside a lot, your “gym” is air conditioned, or you have just been plopped into a hot environment because of a job, start going outside more, NOW. Don’t be a psycho and do a five mile run at noon. Start easy and add activity and duration over a two-week period. Get used to being outside.

WBGT

No, this is not Wimminz, Bisexual, Gay, and Trans or some other tiresome derivative of identity politics.

It’s the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) system and the guidelines for exertion that are based on its values. The WBGT calculates a value based on humidity, wind speed, and heat / solar radiation that creates a heat index. A colormetric system was added to indicate what levels of activity people that are acclimatized and non-acclimatized can undertake based on the index. See below.

| Category | WBGT °F | WBGT °C | Flag color |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <= 79.9 | <= 26.6 | White |

| 2 | 80-84.9 | 26.7-29.3 | Green |

| 3 | 85-87.9 | 29.4-31.0 | Yellow |

| 4 | 88-89.9 | 31.1-32.1 | Red |

| 5 | => 90 | => 32.2 | Black |

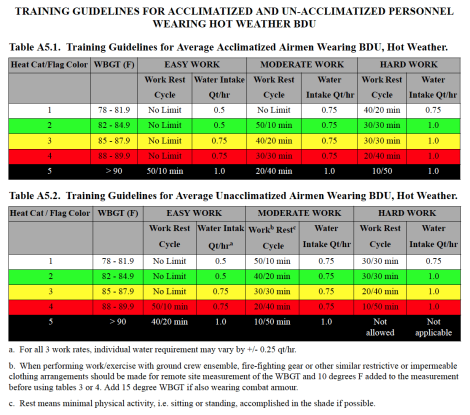

Below is a table of work / rest cycles that was created by the US Air Force for young people in uniform that are acclimatized and not. Keep that in mind as you look at these, and make sure you compensate for your own age, health, and other situations.

Oral Rehydration Solution

Here’s the famous recipe for Oral Rehydration Solution, thanks to Aesop and Ebola. If you don’t have Gatorade or similar, do what you can with this.

- Six (6) level teaspoons of Sugar

- Half (1/2) level teaspoon of Salt

- One Litre of clean drinking or boiled water and then cooled – 5 cupfuls (each cup about 200 ml.)

Preparation Method:

-

Stir the mixture till the salt and sugar dissolve.

If all you have is 1 liter of water and 1/2 teaspoon of salt, that’ll do in a pinch.

Moisture wicking clothes

Flammability issues aside, anything that wicks moisture also speeds evaporative cooling. Pure nylon clothing is very light and great at keeping you cool. Outdoor and camping stores like REI and Campmor have loads of it. If you have to do the BDU thing, try to get the nylon/cotton blends. Cotton gets really heavy when wet because it is hydrophyllic. In a desert environment, it dries pretty fast and helps with cooling, but in humid environments, it just stores hot sweat on your skin.

Watch your pee

If it’s really light yellow to clear, that’s great. If it’s dark yellow or darker, you need to get some water in you. Keep an eye on it. It’s a great indicator of your hydration status. Try to drink about a liter an hour while you are active and 1/2 liter an hour when you are resting. Add salt as needed. Try not to guzzle all at once, but take good sips over time.

If you haven’t peed in a while and are getting tired, have a headache, and generally feel lame, you’re probably dehydrated, so get on it.

Breaks

Take them. If you are out doing cool-guy stuff and it’s hot, make sure you build in times to stop in the shade and give people time to drink water and get rested. The WGBT table above is a good starting point for times. If you are on search and rescue team and two of your people go down with heat exhaustion just when you get to the person that called for you, that’s not good. Keep yourself and your people healthy.

Homework

If you’ve been a couch potato, check out Couch to 5K as a good way to ease into physical activity without killing yourself from heat stroke.

Start acclimatizing for summer and get physical outside for at least an hour daily.

Check your gear and make sure you have some salt in your mess kit in quantities that can be used for replenishing electrolytes if you are going to be in the field a while.

Proper planning prevents piss-poor performance.

References

United States Department of Defense. (2011). Heat-Related Injuries. COL W. D. Farr, M.C., US Army & CDR L. H. Fenton, M.C., US Navy (Ret.) (Eds.) Special Operations Forces Medical Handbook (2nd Ed.). (pp. 6-33 – 6-40). Skyhorse Publishing

Reblogged this on Starvin Larry and commented:

Good advice-pay attention.

LikeLike

I work outside in summer,in NE Ohio,where it’s ofter really humid and hot and have been drinking 1qt Gatorade,then 1 20oz water,then another Gatorade,another water…

Too much Gatorade,and not enough water?

LikeLike

Larry, that sounds really good. Let your urine be your guide! The lighter, the better. You’re doing better than most of America, who rehydrates with liters of Mountain Dew.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have 1 Mountain Dew a day-either the throwback stuff made with real sugar,or the blue stuff that looks like Windex.

Common sense should tell most of us that if there’s sweat pouring off you hour after hour-you need lots of water,and you need either the salt/sugar water recipe you guys gave,or Gatorade,Powerade,etc. to replenish electrolytes.

I never had any heat stroke etc. in all the years I did stamped concrete,but we came close a few times-you have to finish,throw colors with a big brush,and stamp the concrete,so it’s not like just pouring a driveway,or sidewalk-those are done when you are done finishing them-for stamped concrete,it’s another hours work on most jobs.

There were days where we had to spray each other down with a garden hose though.

LikeLike

Larry, you used my two favorite words, “common sense.”

If you are pouring concrete and busting your hump all day, a soda is no big deal, and in fact, can be beneficial from the fast carbs from the sugar. Like you said, if you’re sweating like mad and not drinking water, you are asking for trouble. Sounds like you had a good system to keep each other from bursting into flames.

LikeLike

Pingback: Hogwarts: It’s Hot Out There – Try Not To Puke Too Much | Western Rifle Shooters Association·

I have worked outside in the Arizona heat for many years. I have been purchasing the powdered Gatorade for as long as I can remember. I mix it a little stronger than 1/2 strength. It has always served me well. I did a mission trip to the jungles of Belize and did not bring any Gatorade. I drank gallons of water, but I was one big cramp after two days. I had to eat bananas to make up the electrolytes. I hate bananas, but they got me up and running again.

LikeLike

Glad to hear it Roland. Belize is in one hot and humid latitude.

LikeLike

Great informative article. Thank you. Living and working at 7400 feet plus making jaunts to 10,000 has it’s own set of rules to follow. With low humidity and windy conditions, it is deceptive,because of the lack of visible sweat. Rubber bands placed on my wrist, for each 1/2 gal of fluid consumed, remind me to drink more. Raising an active five year old requires close monitoring of fluid intake and urine. The resulting headaches combined with oxygen deprivation will sideline the Hulk. Working outside,year round, I cover my skin and my head. There is a reason cowboys wear long sleeves and wide brim cowboy hats It is not for show. I appreciate your articles and pass them on to the tribe.

LikeLike

Oooh. High altitude sickness and heat injury. I like you, Knuck. Love your system to stay hydrated. Glad you are finding the articles useful. Big Tom Dorrance fans in this house. Keep up the good work up there.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Defensive Training Group.

LikeLike

Heads up,

That first picture is not altitude or heat related. The gentleman was throwing up because he just ran an obstacle course, ate peeps, ran a 1/2 mile, shot some guns then chugged 72oz of soda.

Check it out at: ColaWarrior.org

LikeLike

The forge where men are made and AKs belong in the garbage can.

LikeLike

I’ve had good results with Pedialyte or its generic equivalent. I find it easier on the stomach than Gatorade or other “sports” drinks. It is also available in an unflavored form, for those who would prefer to avoid artificial flavors and colors.

LikeLike